Legal and regulatory hurdles are playing a major role in stifling competition, hindering productivity growth, and limiting job creation in the economy, according to the World Bank.

In its latest report, From Barriers to Bridges: Procompetitive Reforms for Productivity and Jobs in Kenya, the global institution notes that these barriers remain part of the obstacles the government faces in achieving its targets under the Bottom-Up Economic Transformation Agenda (BETA).

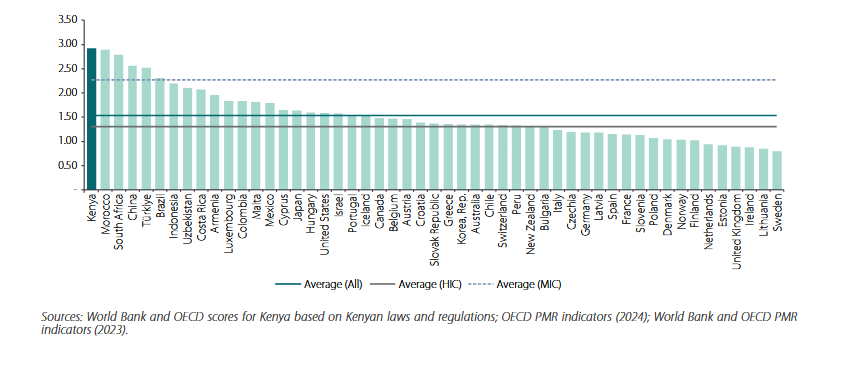

Using the OECD’s product market regulation (PMR) indicators to benchmark Kenya against comparable countries, the report ranks the country as having the most restrictive regulatory environment for product market competition. With a PMR score of 2.92, Kenya stands at the forefront of nations imposing significant barriers to economic openness, well above the average for other middle-income countries (2.27).

While the comparison is partly shaped by a dataset rich with more open, advanced OECD nations, Kenya’s regulatory framework is still notably more restrictive than peer economies such as South Africa, Indonesia, and China, creating substantial barriers to entry, operation, and investment.

These distortions are evident across the economy and driven by three key issues: significant market distortions from a large and often inefficient portfolio of over 200 state-owned enterprises (SOEs) that crowd out private investment; incomplete policymaking safeguards that allow primary legislation to pass without competitive impact assessments; and high barriers to trade and foreign direct investment that protect domestic incumbents.

These challenges manifest acutely in critical sectors. In agribusiness, the fertilizer subsidy program creates exclusive distribution channels that sideline efficient private retailers, while the sugar sector is protected by import tariffs, quotas, and rules binding farmers to specific mills, inflating consumer prices.

The electricity sector suffers from a historical lack of transparent procurement and incomplete implementation of open-access grid rules, keeping power costs among the highest in Africa. In telecommunications, weak infrastructure-sharing regulations and high mobile termination rates contribute to data prices above regional peers, and digital markets lack protections against anti-competitive practices by large platforms.

The transport sector is characterized by preferential treatment for state-owned carriers in aviation, a complete monopoly in rail, and a vertically integrated port authority in maritime logistics, all of which limit competition and raise costs. Professional services such as law and engineering are also constrained by foreign ownership bans, mandatory minimum fees, and advertising restrictions, stifling innovation and consumer choice.

The World Bank proposes comprehensive reform agendas to dismantle these barriers, including reforming SOE governance, discontinuing fiscal transfers to commercial entities, expanding regulatory impact assessments to cover all legislation, and liberalizing trade and foreign investment rules.

Sector-specific priorities include making the fertilizer subsidy program more competitive, introducing open access and competitive procurement in electricity, strengthening regulations to curb market power in telecoms, and introducing competition in transport through liberalization and vertical separation of operators from regulators.

The potential payoff would be immense: implementing these pro-competitive reforms in key input sectors could boost annual GDP growth by up to 1.35%, and increase annual labor compensation growth by up to 2%, equivalent to creating over 400,000 additional formal jobs per year, paving the way for more productive, inclusive, and robust economic growth.